Since its inception as a nation state in 1970, material forms in the Sultanate of Oman – ranging from old mosques and shari’a manuscripts to restored forts now museumified, national symbols such as the coffee pot or the dagger (khanjar) and archaeological sites – have saturated the landscape, becoming increasingly ubiquitous as part of a standardized public and visual memorialization of the past. Its expanding heritage industry – exemplified by the boom in museums, exhibitions, street montages and cultural festivals – fashions a distinctly national geography and territorialized imaginary. But how and why has heritage emerged as a prevalent force in nation building in Oman? My book, Imbibing the Past, Living the Modern: The Politics of Time, History and Religiosity in the Sultanate of Oman addresses this question through bringing together histories of nation building with scholarship on the politics of time and history making. I show how institutional heritage not only becomes integral to a policy of national integration through smoothing the region’s political cleavages but transforms discursive histories into pedagogical, ethical and aesthetic practices that in turn reshape socio-political realities on the ground. While scholarship has examined the impact of modernity on contemporary Muslim societies in the realms of education, law and the media, my research project is a study of how forms of history and the institutionalization of material heritage (turāth) recalibrate the Ibadi Islamic tradition to the requirements of the modern political and moral order in the Sultanate of Oman. I demonstrate that even as the modern Omani state diagrams an orientation towards the past, through the grammar of heritage, it translates and thus transforms the discourse and practice of Ibadi Islam itself. Through this process it reconfigures the socio-political and ethical fabric of communal relationships that once characterized a sharīa society, rendering them more amenable to modern state-building efforts. In forging this national imaginary, it effectively transforms the modality of the relationship between politics and religion, enabling new and different ways to perceive and organize historical experience.

Based primarily on over 20 months of ethnographic fieldwork (2010/2011 and the summers of 2015,2016,2017) in Muscat, the capital, and Nizwa, once the administrative and juridical centre of the Ibadi Imamate, the book analyses the relations with the past that undergird the shift in Oman from an Ibadi shari’a Imamate (1913-1958) to a modern nation state from 1970 onwards. The book explores the material, ethical and social significance of key objects and sites and the dynamic changes in the work they do over the course of the 20th century, specifically the Nizwa fort and the dalla, coffee pot. These become sites for tracking transformations in forms of history, religious and political authority and modes of sociability. This ethnographic investigation documents the implications of shifting history away from a form of cognition and toward institutionalized material practices that become points of tension and ambiguity that condition daily life.

The book is organized around three key questions: (1) how are the practices of public history that is heritage tied to questions of nation building, historicity and religion; (2) how does the institutionalization of this history affect the heterogeneity of life’s daily interactions and relationships and (3) what are the primary fault-lines along which conflicts over the national historical narrative occur and why (ethnicity, tribe, religion). This discursive genealogy is set against an ethnographic account of contemporary struggles over the meaning and implementation of history as part of state sanctioned memory based on recent fieldwork I conducted between 2009-2011. I worked with ministry officials, museum curators, historic restoration experts, religious scholars, human rights activists and ordinary families who think through accounts of the past in order to intervene in the present through seeking to make sense, reinterpret or even transform the conditions of modern political belonging.

Many recent works have studied material heritage in the Gulf States as part of national projects of citizenship and collective belonging. These studies argue that in the Arab-Persian Gulf, certain cultural practices and symbols of recent origin are mobilized to provide a sense of belonging for those subjected to the ravages of a Western-oriented modernization. Examples include the built form of the National Museum of Qatar in the shape of the desert rose, historic restoration projects such as Dubai’s al-Bastakia quarter or the phenomena of newly invented televised traditions of camel racing in the UAE or pearl diving in Kuwait. This type of perspective considers the significance of heritage practices in terms of their ability to instill ideologies, thus downgrading their role to a reflection of statecraft, strategic maneuvering and political governance. What tends to get lost in such scholarly accounts is how the pedagogical circulation of material objects, sites, and architectures engenders forms of public history that substantiates new realities. My book, “Imbibing the Past, Living the Modern: The Politics of Time, History and Religiosity in the Sultanate of Oman,” challenges such accounts by showing how the systemic public visibility of these material forms has the potential not only to overcome violent differences, delineate social relationships and the ethical sensibilities of their audience, but also figure as points of tension and conflict in ways that become integral to the norms of modern daily living. In contrast to existing scholarship that tends to focus on the ways in which the Gulf countries construct an unfolding ‘national story’, I ask how the meanings and practices of history making in the Sultanate of Oman moves beyond legitimation towards producing modern governance. I examine how, heritage as a paradigmatic mode of inclusion and exclusion, regulates religion and political life, making specific imaginaries of emancipation and constraint possible for a national audience.

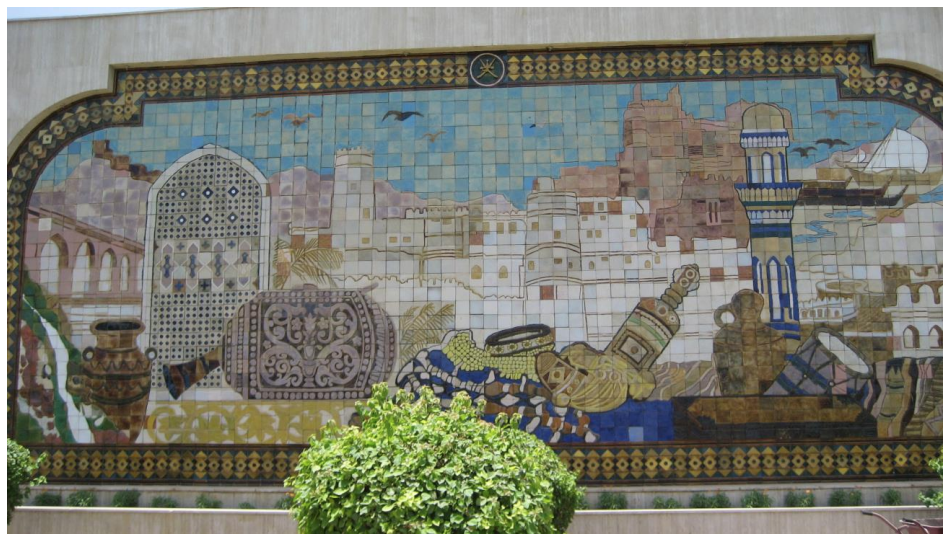

But the construction of the heritage project in modern Oman has also necessitated the reconfiguration of the public domains of history and Islam as seemingly separate and autonomous, erasing any awareness of the socio-political and ethical relationships that once characterized Ibadi Islamic rule (1913-1958). The result is the transformation of what was once a sharī‘a society through practices of progressive historicity. Ibadi Islam was constitutive of a distinctive Islamic sectarian ethico-political system, whose last manifestation arose and ended as the direct consequence of British military and economic colonial intervention in the twentieth century. The sharī‘a community of the Imamate recognised and worked within a socio-political order structured around hierarchies grounded in descent, tribal lineage, occupation and wealth. The Ibadi sectarian tradition that predominated for more than a thousand years in the area is still in evidence in the great fortresses, watchtowers, walled residential quarters, and in mundane objects such as the dalla (coffee pot). Their form and function facilitated socio-political practices and tribal relationships that embodied an Ibadi sharī‘a community and way of living. These material objects, settlements and sites were situated within the modes of reason and material practices that fashioned a distinctive theologically defined space of a community marked by difference, rather than the homogeneity of the nation state.

The institutionalized practices of history making in Oman have marginalized alternative understandings of the past, subsuming those ways of life and authority considered incompatible with entrenched national histories. Both historic sites and material objects become tethered to fundamental values and realities of national life (such as equality, entrepreneurship, pluralism, hard work, family ties) that define the ethical actions necessary to become a modern Omani citizen through the framework of tradition.

The result is the official expunging of alternative histories such as those of British informal governance, genealogy and Arab tribal belonging as well as the careful configuration of Ibadi Islam, its doctrine, and practices. However, I demonstrate that even while national homogeneity conditions the way people ethically work on themselves by evoking such forms of heritage as the Nizwa fort now a museum, its old suqs and residential quarters or the dalla (coffee pot) by way of example, it also generates anxieties and emotional sensibilities that seek to address the erasures and transformations of the past. These include an unacknowledged legacy of slavery that was once an integral part of Ibadi sharī‘a society, the spectre of old tribal tensions, lineage and occupation hierarchies as well as non-Arab, non-Ibadi mercantile communities such as the al-Lawati, originally a Shi‘i community from Sind, who were once stalwart allies of the British/Sultan and are now Omani citizens.

Amal Sachedina

Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Institute for Middle East Studies Elliott School of International Affairs George Washington University 1957 E Street NW, Suite 512 Washington DC 20052