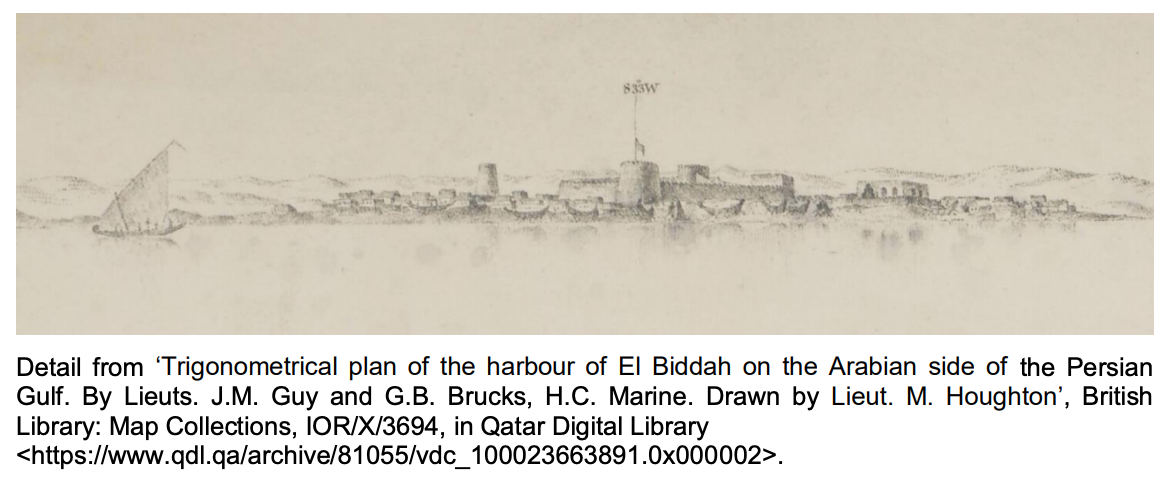

This project uses the coastal views, charts and sketches produced by British mariners in the Persian Gulf over the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to observe changes in watercraft and the cultural landscapes of organised violence. This hydrographic iconography was principally aimed at ensuring the safety of navigation of commercial vessels within the Gulf, but surveyors were progressively more concerned with organised violence over this period, until the agreement of formal maritime truces between indigenous polities and the British. As part of a broader PhD enquiry into the influence of organised maritime violence on the indigenous watercraft traditions of the Gulf, this particular project examines one of the more prominent classes of iconography relating to maritime violence in the Gulf. Indigenous watercraft of the western Indian Ocean, and especially those of the Persian Gulf, are poorly represented in the archaeological record, particularly from this era of European intrusion. My PhD research therefore uses Indigenous, European and Indian iconography, such as rock art, graffiti and manuscript paintings, together with limited archaeological evidence, to investigate the changing nature and use of vernacular fighting vessels.

Hydrographic iconography of the Gulf produced over the period c.1700–1850 appears increasingly concerned with military access and freedom of manoeuvre, and less so with safety of navigation. Watchtowers, fortifications and minarets that aid position finding offshore are still depicted, but khors, lagoons and low earthworks that have no role in offshore navigation are increasingly shown as well. The use of these latter areas for concealment of watercraft or retreat from pursuit is widely attested in historical sources, and their exposure by iconographic depiction represents a process referred to as ‘writing down the coast’. British mariners, hydrographers other officials created charts and views that depict the indigenous fighting vessels and landscape elements of the regions in which they were engaged. Regional societies rarely configured vessels exclusively as warships, so the range of iconography applicable to this study includes depictions of any indigenous vessels BFSA Small Research Grant Report Mick de Ruyter, +61 481 946 657, mick.deruyter@flinders.edu.au 2 or maritime cultural landscape elements associated with organised violence. The spatial and temporal associations of these elements are particularly well represented in hydrographic material, which also precedes the naval architectural drawings and photography of later ethnographers who generally observed indigenous watercraft after the agreement of the maritime truces.

The BFSA grant has funded archival research in the UK at the National Archives, the British Library and the National Maritime Museum. While some relevant data is now available online, such as through the Qatar Digital Library project, the National Archives holds a significant collection of coastal views and charts of the era formerly curated by the Admiralty Hydrographic Office. Mariners recorded views and sketches in their journals or logbooks, and military expeditions often included both official and unofficial combat artists whose works are also relevant. Using these sources, this research aims to identify the temporal, spatial and structural changes in the way vernacular watercraft were used for organised violence in the Persian Gulf.